But there’s a kicker: personal responsibility

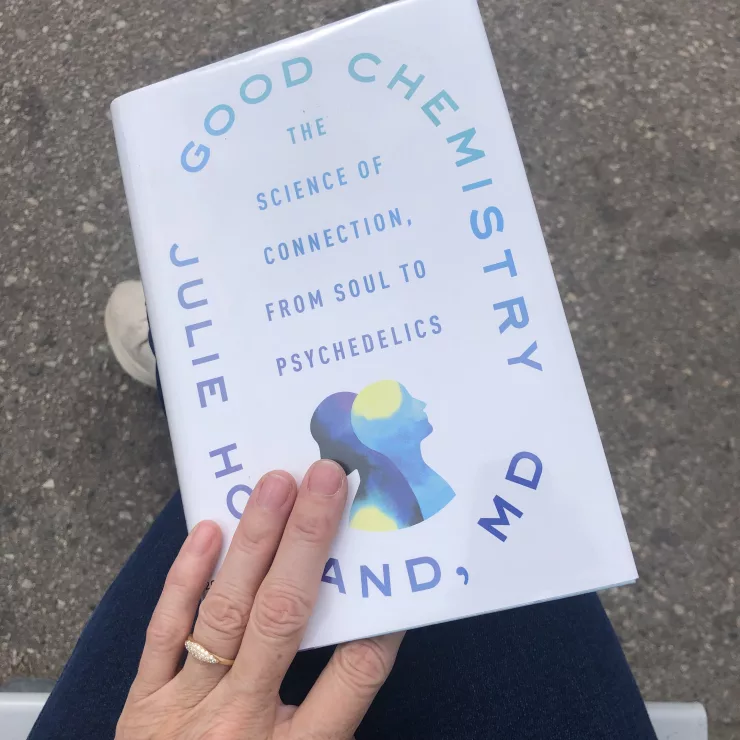

I really admire Julie Holland, whose book puts her in groundbreaking territory. In it, she says that SSRI’s don’t really work. And in fact, big pharma and the whole model of medicine based on prescriptions as the solution doesn’t work.

In the early pages of her book, Holland describes how frequently prescribed mood-altering drugs like Prozac and Zoloft, as well as stimulants like Adderall and Ritalin, are masking our underlying ailment, which she describes as loneliness. By suppressing the symptoms, we render ourselves unable to solve the bigger problem.

Holland is not afraid to say that one of the major problems that’s leading to our loneliness is device addiction. She explains how, when parents pay more attention to their phones than to their babies’ coos and cries, they put their childrens’ future mental health at risk.

Childhood trauma is THe elephant in the room

But it’s not just devices. It’s all of our addictions, which are really just a sum total of all the intergenerational traumas that are stored in our bodies. Oh, and speaking of addictions, says Holland, the treatments we have for substance misuse disorders these days don’t work.

It’s a whole industry that she’s talking about, and the explosive bit of the story is that Holland, a psychopharmacologist and psychiatrist, worked for a decade in the psychiatric emergency room at Bellevue Hospital, a public hospital in New York City.

“In the addiction business,” she writes, some clinicians are slow to adapt, and there is a “tyranny of dead ideas” that refuse to die. Concepts like “clean” or “dirty” just don’t work anymore to describe people involved with drugs.

But what does work?

The answer to our problems lies in a more holistic approach to healing. Of course she’s not suggesting people suddenly stop taking their SSRIs. She’s saying our culture needs mass treatment for childhood trauma and mass education about how to regulate one’s own nervous system.

Non-intoxicating CBD can help too. Meditation, can help, and so can putting down the device, reading a book, being in nature, and reducing your compulsion to buy things.

Connection is the medicine we need

I think it’s pretty explosive that a doctor is saying we have a mental health crisis on our hands, but medicine as it exists today is not helping. It doesn’t have the tools or the mindset. Instead, Holland asks people to strengthen the connections they have in their lives. How can we get more connected with ourselves, our partners, our families, our communities, the earth, and the cosmos? That’s how we’re going to feel better.

“We need outside-the-box solutions to our current psychospiritual problems,” she writes. Then she goes on to explore what psychedelic experiences might mean for our collective yearning for connection. By the end of the book, Holland states plainly that “these plant medicines are good for the soul” in a way that antidepressants and tranquilizers aren’t. “Psychedelics dispel the illusion of separation.”

The effect, she says, stems from the fact that psychedelics create increased connectivity in the brain, between areas that don’t usually communicate. But even though this book sells itself as a science book, Holland concludes that there is far more to psychedelics than what they do in the brain. It’s really about integration, and how people apply the messages they receive on their trips.

Psychedelics have potential to benefit families

Holland acknowledges the importance of a therapeutic model for psychedelics, but says sacred and recreational uses are valid, too, and these modes may be more accessible and more useful for the masses in the long run. She also writes briefly about “psychedelic parenting” which can “help you be more open, connected, attuned compassionate or creative.”

“Anecdotal stories of parents benefitting from their own psychedelic explorations and education abound,” she says, explaining that parents should take their trips when the kids are with a sitter. “It’s controversial, she admits, but “parents can’t connect fully with their child if they’re not fully connected with themselves.”

Holland interviews a psychedelic advocate, Katherine MacLean, who proposes that psychedelics should be available not just in a clinic, and not just for people with a diagnosis of anxiety, depression or PTSD. Says MacLean in Good Chemistry: “We have to remember that the bar for entry shouldn’t be safety. It should be education and informed consent.”

Empowerment for the individual is a radical idea

That’s threatening to some people, MacLean goes on to say. “The psychedelic experience teaches you about how to live your life… And that’s actually the most radical thing about psychedelics — they give every single individual the empowerment to access the divine in themselves. There’s no intermediary. That’s also the scariest aspect. It scares the medical doctors. I think it rightfully scares governments. It’s a lot of power that you’re reminding individuals that they have.”

But its encouraging for the rest of us. There’s a better way to live than our current reality. And if the current movement toward decriminalization and legalization of psychedelic substances continues, we will soon have tools to help us get there.

Published by